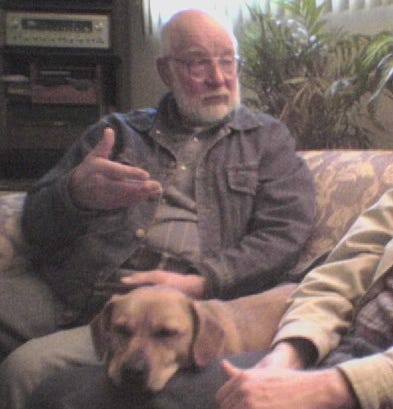

Dad Gerry

I always used to send my father-in-law a card for Father’s Day.

Photo by Owen Bjørnstad

For the first few years, they were easy enough to find: Gerry was a man of plain tastes and so I chose dignified cards with simple words on a warm brown background. A couple of years in, however, it was becoming difficult to find a card that I liked that I hadn’t already sent him; after four or five years, the selection simply dried up. Oh, there were Father’s Day cards galore in the store: cards for fathers and stepfathers, for grandfathers, for husbands, for brothers, for friends, there were even Father’s Day cards from the cat or the dog. For fathers-in-law, however, the choices were minimal.

In practical terms, this was not too much of a problem. It is hardly inventing the wheel to buy a blank card and write Happy Father’s Day inside, and Gerry was just as happy either way. But the underlying message – that a father-in-law was not worth a great deal in the way celebration – seemed to me to be missing an important, albeit too often overlooked, emotional point. Because if any of us is lucky enough to have a man in our life who is a good man and treats us and others with kindness and respect, then whom should we expect to have to thank for that but his father?

I loved Dad Gerry. He was a farm boy from North Dakota and proud of it, who came to California with his high school sweetheart looking for work in the early 1940s, and, with the exception of four years in the military during the War, stayed on the West coast for the rest of his life. He married his North Dakota girl and had four children with her; sadly their marriage fell apart later, but Gerry, who was a man of impeccable class, did everything he could to make the split as easy as was humanly possible for everyone involved. He waited to leave the family home until Mr. Los Angeles, his youngest child, had embarked on his adult life; he later asked his children’s blessing before he entered into a new romance; he surrendered the roomy family ranch house in fashionable Westside Los Angeles to his ex-wife, and took himself off to a small town in Oregon to live in a tiny trailer he kept as neat as a new pin, near the home of his younger sister, the redoubtable Auntie Ann.

Gerry was six feet tall, had massive hands and a commanding voice, and wore farmers’ overalls throughout his life; he liked strong coffee, which he called, approvingly, “Norwegian gasoline,” and hearty home cooking – I once sent him a recipe for an egg scramble made with ground beef, spinach and cheese, and could hear his tastebuds salivating clear from Marion County; he loved animals and, surprisingly to some people, poetry, over which he and I had quickly bonded; and he had an endless supply of groanworthy jokes about a couple newly arrived from the Old Country called Ole and Lena, of which I mercifully only now remember one: it was a seasonal joke in which Ole, delicto in some sort of flagrante, tried to pass himself off as a set of Christmas bells (I guess you had to be there), and when someone tried to ring the bells (I guess you really had to be there), cried in a strangled scream “Yeesus Christ! Yingle yangle!” – a punchline Gerry was barely able to deliver through the wheezes of hilarity that attacked him whenever he reached it, time after time after time after time. Occasionally, to the family’s collective horror, he would find someone who would enjoy the Ole and Lena jokes and beg him for more: at which point we would all creep quietly away until at last the boom of his voice had died down and we would know it was safe to return.

Like many of his family, Gerry was mildly psychic: he could divine water and sometimes knew things would happen before they actually did – a fact he attempted to deny later in life but which was briskly confirmed by Auntie Ann over a pancake breakfast in the trailer with the immortal line, “Oh, yah. Happens all the time. Pass the syrup.”

Gerry worked as a contractor, and although he was never enough of a businessman to make appreciable money from it, he was dedicated to his craft to the point of fanaticism, and taught all three of his sons, and his daughter too, to look at the physical world with the same level of care and attention that he did himself – a series of lessons that Mr. Los Angeles, who had worked with Gerry for a while as a young man, has never forgotten. Mr. Los Angeles once spent some time helping an old college friend and her wife with house repairs, three days into which both women approached him with serious expressions and sat him down for a talk. “We love you,” they said. “And we very much appreciate what you’re doing for us. But we have to warn you that if you say, ‘My Daddy always taught me,’ one more time … we’re going to have to kill you.”

Gerry taught his children other skills beyond handiness with a hammer. He taught them to be honorable and unpretentious; to judge no person by their bank balance, measure of sophistication or level of education; he taught them to be kind to animals as well as to people; he taught them to nurture their funny bones as well as their intellects. Gerry was not a saint. He was as stubborn as a mule; had a volcanic temper and the tact of a Skilsaw; he could too often be, as Mr. Los Angeles was given to describe him (mostly) affectionately, “a cantankerous old buzzard.” But he was a good man; and, as a father to his sons, he not only taught them, but provided a superlative example for them, how to be good men too.

Gerry died on a glorious summer morning up in Oregon, after a long and painful illness, towards the end of which he had been wracked by delirium. On the next to last day of his life, he suddenly and shockingly came to his senses for just a few moments: he looked up at the bearded six feet of Mr. Los Angeles, who was helping to take care of him, and said, clearly and firmly, “I know you. You’re my little boy.” A day and a half later, as the dawn was breaking over the fields beyond the window, with Mr. Los Angeles still at his side, he left us.

Every man hasn’t been so lucky as to have a father like Gerry. Some men have had fathers who were disappointing in any manner of ways; some men have never had fathers at all. But Mr. Los Angeles did have Gerry; and he was lucky for it, and as his wife I am lucky tenfold.

We love you, Dad Gerry, and we miss you. Maybe not the Ole and Lena jokes. But we miss the other parts of you like crazy and always will.

Brought a little tear to my eye xx

What a beautiful tribute to your late father-in-law as the holiday honoring.fathers approaches. In knowing Owen I see where he gets his humor...and.kindness.